I have seen Sevda Semer’s works in the second week (28 May-6 June) of Check-in, curated by Marcus Graf, the first exhibition of the Bulgarian-origin Collect Gallery that has recently opened in Tophane. I would like to introduce the artist Sevda Semer to 5harfliler, who works on paper and fabric, as well as producing installations, sound, video and performances on themes, to my understanding, such as the manifestation of personal feelings, the individual’s positioning in society, and the gap between subjective perceptions of reality and social categories.

First of all, thank you for accepting my interview offer. On your website you refer to the rich library consisting of albums and biographies of Russian and German artists in the house where you grew up in Bulgaria during the 90s, which undoubtedly guides your text-based production. In line with this, could we get to know you and your artistic practice?

It still feels strange when I’m even called an artist. I remember a curator once telling me: “Sevda, it’s about time you understood you’re indeed an artist!” A significant part of my work stems from not daring to call myself one and looking for expressions outside of what I imagined was “official” art. But books always felt close and maybe that’s why I work so much with them. I work with visual diaries, in which I document certain states or stories. I also paint, sometimes abstractly, sometimes heavily involving text. There is a a non-visual part of my work —my audio recordings, usually of my own voice narrating a story. Text in a very broad sense of the word is important in all kinds of ways to me, sometimes working with a specific word even. I’ve done performances, videos, sculptures, I like working with textile… I have many desires so I have many ways to express them.

You are currently based in Copenhagen. How do you spend your days there? How do the living conditions of the city affect the lifestyle of the artists and your personal production practice in general?

This is a big question —and because I’ve only moved here less than three months ago, I can only begin to answer it. When I was very small, I couldn’t decide what I wanted to do, so I made a business card out of an A4 piece of paper that held my 7 different professions. One for every day of the week. The concept of rest can only appear after one has worked, of course. I think I still carry some of this desire for living widely, living in many different careers. Partly because of that, partly because I wasn’t able to afford art school, I’ve always had another career to complement my art. This isn’t a burden, but something I enjoy. So among my many other projects —book reviewing, writing, a queer book club and other LGBTI and human rights projects to name a few— the last few years I’ve become quite interested in learning a craft and seeing the difference between it and art. Because I’m absolutely obsessed with baking sourdough bread at home, I became a baker when I came here. Copenhagen is one of the places with the best bakeries. It’s interesting how many artists I’ve met in bakeries, actually. Maybe there is a reason why we’re flocking to baking in particular in this city. This is beginning to change my art as well, of course, like any major change would. But it’s too soon to be saying how exactly. Other than that, my studio currently is existing in the fringes, which I again enjoy for the moment: because our landlord is required by Danish law to have storage space for everyone in the building, and because this is currently unused, I’m having my studio there, on the ceiling. I like the fact that my studio is currently a storage space. I store all kinds of things in there.

Having talked about your relationship with the idiosyncratic dynamics of the city, I would like to move on to the framework of identity. What does Check-in, the first exhibition at the Collect Gallery, bringing together works by four Bulgarian artists, say for you in terms of identity politics? Apart from Sofia, you lived in London, and now you are in Copenhagen. While the universal language you have established in your works is immediately visible, to what extent does the framework of locality and “living away from home” in general determine your production?

This really made me think about whether or not an exhibition can say anything about me in terms of identity politics. I hope it’s only able to say something about the art. I find a separation between my art and myself to be a healthy thing – maybe especially since I work with the personal so much, I can’t afford to identify completely with my art. But the question is also making me remember how a close friend and an artist, who lived outside of Bulgaria for many years, was telling me what it was like to return to her home country. She said it feels like she was let loose in the wild. By this she meant that when you’re living away from home, it’s easy to choose some parts of yourself to carry with you, and forget others —and of course we always tend to forget the more difficult ones. So returning is always important in a way— to make peace with these wild parts. It’s interesting to see how you transform with new places, with new languages. It does determine my work in many ways, some quite obvious, others I’m probably not even detecting yet. For example, when I’m in Bulgaria, I tend to use a lot more Bulgarian in my works. When I’m here, I use a lot more English in my text pieces. Even though my public remains the same —I mean it isn’t important for someone seeing this exhibition in Turkey for example where I personally am living.

Among your video arts, “Performing writing” is particularly interesting in which you talk about your textual diaries. Based on Ludwig Seyfarth’s comment, which you share on your website, can I ask you whether the person speaking in the video is your “private self” or “public self”?

Ludwig suggested I make a video in which I talk not about my practice, but about my writing. I knew two things – firstly, to see how that can turn into art, and secondly, I wanted to talk about my private diaries that I’ve kept since I was a child. Talking about something that by definition remains hidden. In this video however, I’m performing in a very pure sense of the word. The process of making it was that I wrote down what I wanted to say, recorded my voice reading the text out loud, and then played that on the headphones you see me wearing in the video – while saying the words out loud as if I’m speaking spontaneously, using the microphone of the headphones. I borrowed part of the technique from verbatim theatre. Of course, my cadence is completely off compared to someone that just improvises what they’re saying – it was interesting to hide in the video, in a way, when I’m talking about this hidden work. So the answer is probably that my public self is performing my private self.

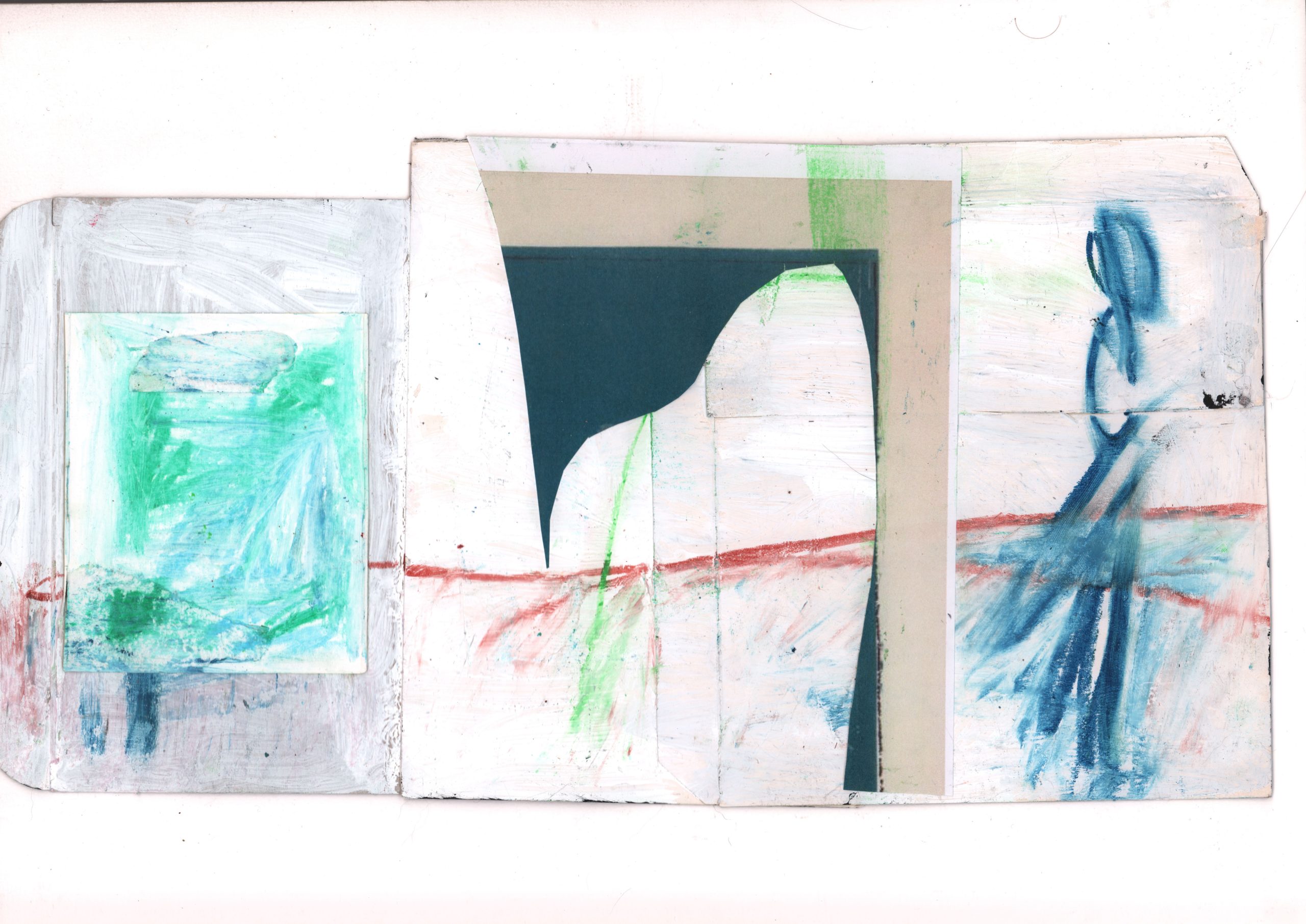

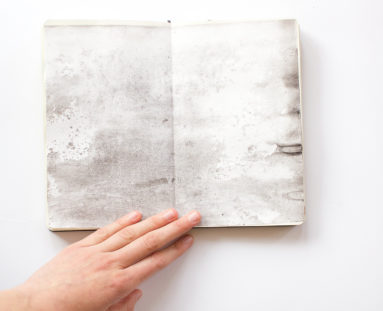

Visual Diaries, 2017.

Visual Diaries, 2017.

Can you provide us some perspectives as to which the concepts of bodily memory, self-construction and identity formation can be viewed in your works that are based on text, history and narrative? How do illegible words, sentences, and scribbles form multi layers in your artistic production?

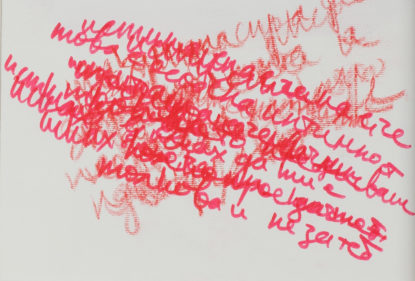

Language was the first way that I touched the world and enjoyed its touch. It’s tremendously important to me. At the same time, I always leave space for the imagination of the public. Illegible words can mean different stories to different people at different moments. Almost for a decade now I’ve been doing a series that I call The Letters – in these I keep writing and writing letters at very emotional moments, rotating the paper and layering the text, until it starts looking like a drawing. It’s always nice to look back at one of these some time after creating it and seeing that I’ve forgotten what the specific letter was about or perhaps also who it was addressed to. In that way, not only the public can be free to imagine, but I can in a way also feel a sense of freedom – I have expressed the feeling and moved on, unrestricted by the past.

The letters, pencil, marker.

Your paintings include works centered on the nervous system and the body which remind me of somatic experiencing. For example, we see two legs answering “Yes?” to the question “Have you been here before, body?”. For me, some of your works dwell upon the condition of alienating from oneself and one’s environment. I understand that you reflect on these “disorders” from a transformative angle, which are also discussed in terms of body politics, feminism and queer theory. What would you say about this?

The drawings that explain the feeling of dissociation and depersonalization were made seven years ago. Looking at them, I can’t help but notice how much white space there is, how delicate the colors are, almost as if they’re not there… Which I see again as a form of dissociation —and none of these decisions were made consciously. I remember these drawings being very scary to me at the time. Now they aren’t, they just make me feel sad. To answer the second part of the question, I’ve made art about being queer and about being a woman, and of course as both I inhabit a body. To me it’s quite important not to divorce the politics from the simple fact of living. So I like bringing the image or the experience of bodies in all kinds of places where we intellectualize.

Finally, can you tell us about the concepts and works you have been working on lately? Thank you so much…

I’m currently concentrated on my project which has lasted five years – it’s a diary on love in many formats. I’m in the last 6 months of it, so it feels like saying goodbye. This makes me want to create more and more for it – it will be difficult to separate from it after all this time, so at least I want to know I gave it all my energy. I often work with time, or in large series like this. And my love diary has a lot of things in it, which of course I couldn’t anticipate when I started it – it’s a lot more dynamic than anything I expected. Other than love, it has the end of a relationship in Covid isolation, all kinds of emotions around that, then after a while flirting and dipping in and out of short love stories, then falling in love in a very big way and moving to another country to be with my partner as the war in Ukraine was starting. It has a lot of feelings and events. At the end, it will consist of books, video, audio, textiles, objects, drawings. I’m still making work outside of this project, but my energy is mainly concentrated there. And the final thing left now is to say thank you for your illuminating questions, and to the reader for also being here.

Five Years on Love and Intimacy, 2018-2023.

Five Years on Love and Intimacy, 2018-2023.

Cover photo: Sevda Semer