I met Nadin during her residency at the Tarabya Cultural Academy, where she was granted a tandem scholarship to create a collaborative work with Özge Açıkkol and Güneş Savaş from the Oda Project. Responding to the open call, I attended one of their picnic meetings at the Ataturk Urban Forest in August, and was introduced to the wool spinning technique by Nadin. During this meeting, I got the chance to think together with and talk to with several other women about issues such as cleaning, motherhood and care work during the COVID-19 pandemic. The meeting was definitely out of the ordinary — at least for me; it consisted of moments where we took turns listening and speaking, then collectively remaining quiet. I was paired with Nadin; first, she spoke for three minutes, we keep silent for another three, and then it was my turn to speak for three minutes. This method was transformative, to say the least. And so, I would like to introduce Nadin Reschke, whom I felt close to, to 5harfliler.

Dear Nadin, thank you for taking the time to do this interview. Shall we begin by getting to know you personally and as an artist?

I define myself as an artist, although I work in a lot of different social contexts. I organized drawing classes in prison, worked in a women’s shelter and ran an art studio for and with formerly homeless women in Berlin. I was born in the GDR, and witnessing the fall of the Berlin Wall and the changes in the political system strongly influenced my understanding of art. Central to my work is creating and facilitating processes and situations of communication. I live and work in Berlin but many of my works are created in transcultural contexts. A feminist conviction shapes my struggle and how I see the world.

Nadin Reschke

One of your texts refers to your usage of “fabric and textile as a sculptural material, as carriers of collective history, identity, and individual experience”. How does fabric and textile help you do that?

Yes, fabric or textiles as a material already carry a history in themselves in terms of how they have been produced, touched, used and worn. Humans have spun yarn to create fabric from the very beginning. And fabric acts as a second skin. We dress with fabric, we sleep and cover ourselves with fabric. It creates part of our identity every day. I use that in my artwork in a playful way. Since I work on feminist issues collaboratively, I invite women to join a common process, for example to dress up according to a given question or place. In Is the Future Female? (2020), we looked at the history of Spreepark (a former amusement park in East Berlin) through a very personal and biographical female lens. The dress and textiles here function as costumes which invite everyone involved to freely talk and share subjective experiences. The history of the park from the end of the war in 1945 until after the fall of the Wall is an exclusively male story. Since women were neither present nor even heard in these planning and decision-making processes, I ask: How can the female gaze contribute to, influence or challenge the future of Spreepark today? How can our specifically female perspective become visible on this park, and what wishes do we formulate for its future?

I would say that your work speaks closely to the statement, “personal is political”. Workshops constitute an important, or more accurately, an essential aspect of your artistic creation. Why? What makes workshops so important for your work?

Yes, you are totally right. My practice is collaborative: I work with people, not alone. I am interested in the production of difference —as heterogenesis. Acting as a group, be it a defined, cohesive or loose conglomerate, always creates a multitude of positions and viewpoints. And I believe that the real challenge of our society is how to live with such heterogeneity and plurality. I don’t like to use the word “workshop” —for me it’s rather the invitation to a collective process.

You’re currently in Istanbul at the Tarabya Cultural Academy for a joint project with Özge Açıkkol and Güneş Savaş, two of the three founders of the Oda Project. What is the project that you are currently working on as a group? How did you all meet and decide to work on this?

We met in 2004 in Istanbul. I was traveling at the time with my project so far so good (2004-05) with a tent made of white transparent parachute silk, which I had designed myself and made to fit my own body measurements. On my two-year journey with the tent, I passed through fourteen different countries including Turkey, Iran, Pakistan and India. I invited and offered residents and artists along the route the chance to use the tent temporarily for joint actions and to embroider images and texts to its fabric walls. The Oda Project invited me to embroider the tent with their neighbors in their Galata project space. We spent a fantastic two weeks together, learning from each other while embroidering the tent with Burcu, Emine, Ayse and the other neighbors. I learned so much about Istanbul, the ongoing gentrification at the time, the need to adapt and resist. It was also the beginning of a great friendship. Since then, we have collaborated on more projects. The invitation to Tarabya Cultural Academy gave us the possibility to continue our joint work with a new proposal. We felt the need to look back and digest the past two years as artists but also as mothers in terms of pandemic experience. We wanted to know what we encounter when we share our experiences with the pandemic in a collective process with all women and everyone who identify as women. The pandemic has acted as a catalyst of fragility. Gender roles have shifted. Do we experience a push-back? Together with other women we wanted to create a space in which we could share and research the effects of the pandemic isolation on our (artistic) production and daily reproduction by raising a series of questions on post-pandemic normalization, sharing of care work, support and solidarity mechanisms, invisible domestic labor, and new strategies that women invented during the pandemic. We met each time in a different park throughout the city, claiming public space with blankets which were showing our main questions.

I know that you have a symbiotic relationship with this city. How does Istanbul alter your understanding of yourself both as a human being and as an artist?

I always fall in love with Istanbul whenever I live here (2004, 2007, 2022). This does not happen to me in other cities. I don’t know why. I am surrounded by such a stunning beauty while at the same time witnessing real cruelties, especially when it comes to women. How can both be so close and parallel? Istanbul is a city full of contradictions, and of struggle. And that affects a lot of my inner struggles as a woman, as an artist. It feels productive, chaotic, driven. I am out of my comfort zone. Saying that, I understand I am in a very privileged situation being a resident at Tarabya Cultural Academy. If I lived here as a woman artist and a single mother without these privileges, I would not know how to survive.

During our meeting, you were asked by a group member if there was gender inequality in Germany, or more generally, in the Western world. You replied that the world as a whole is so far away from any kind of equality in any sense. But also, you defined your feminist stance as an ongoing endeavor to fight against “internalized patriarchy”. How does this term unfold in your life?

It’s a given fact that we struggle with patriarchy in everyday life. Because we have internalized it, it disguises itself and we sometimes don’t even recognize it. That’s why I see it as a lifelong process of learning and uncovering.

Can you tell us about your project I Would Rather be a Lover Than a Fighter? How do you experience the urban space, which makes you furious about the “male norm biography”?

I started I Would Rather Be a Lover Than a Fighter in Bangalore shortly before the pandemic, out of a personal need and my everyday experiences as a woman. The city intimidated and unsettled me. How do I move, how do I look, what kind of gestures do I use? How are these experiences influenced by my gender? I felt restricted on many levels, also in my physical movement. I started attending dance classes to compensate for that. When I walked home after class in the evenings, I felt uncomfortable. Male friends told me not to worry. It is not that I am worried, but my embodied experience cannot be denied. Cities aren’t built to accommodate female bodies, female needs, female desires. Just to give a recent example, I was in Beyoglu for some days and suddenly got my period. Since I arrived in Turkey my menstrual cycle adapted to the women I met here. Everything went out of the routine. I had forgotten my menstrual cup. It was bayram and most places were closed. I spent hours and hours running around trying to find shop that was open to sell tampons. I was exhausted in the end, and furious. Half the population is female and period products should be available everywhere 24/7. It continues with inaccessible public toilets… safe traveling, parks and pavements inaccessible to prams.

Lastly, can you tell us about some of the current concepts that you have recently been reading on or thinking about? What is next as per your artistic production?

I have spent these last days in Müze Gazhane, setting up a presentation of our current project Words to Spin as part of the Istanbul Biennale. It is exciting to share some of the process and questions discussed with a wider audience and to get some feedback. Back in Berlin I have a solo exhibition coming up in in November, which is a continuation of I Would Rather Be a Lover Than a Fighter. For this I am re-reading Leslie Kern’s Feminist City and totally go for her ongoing experiment in living differently, living better and live more justly in an urban world.

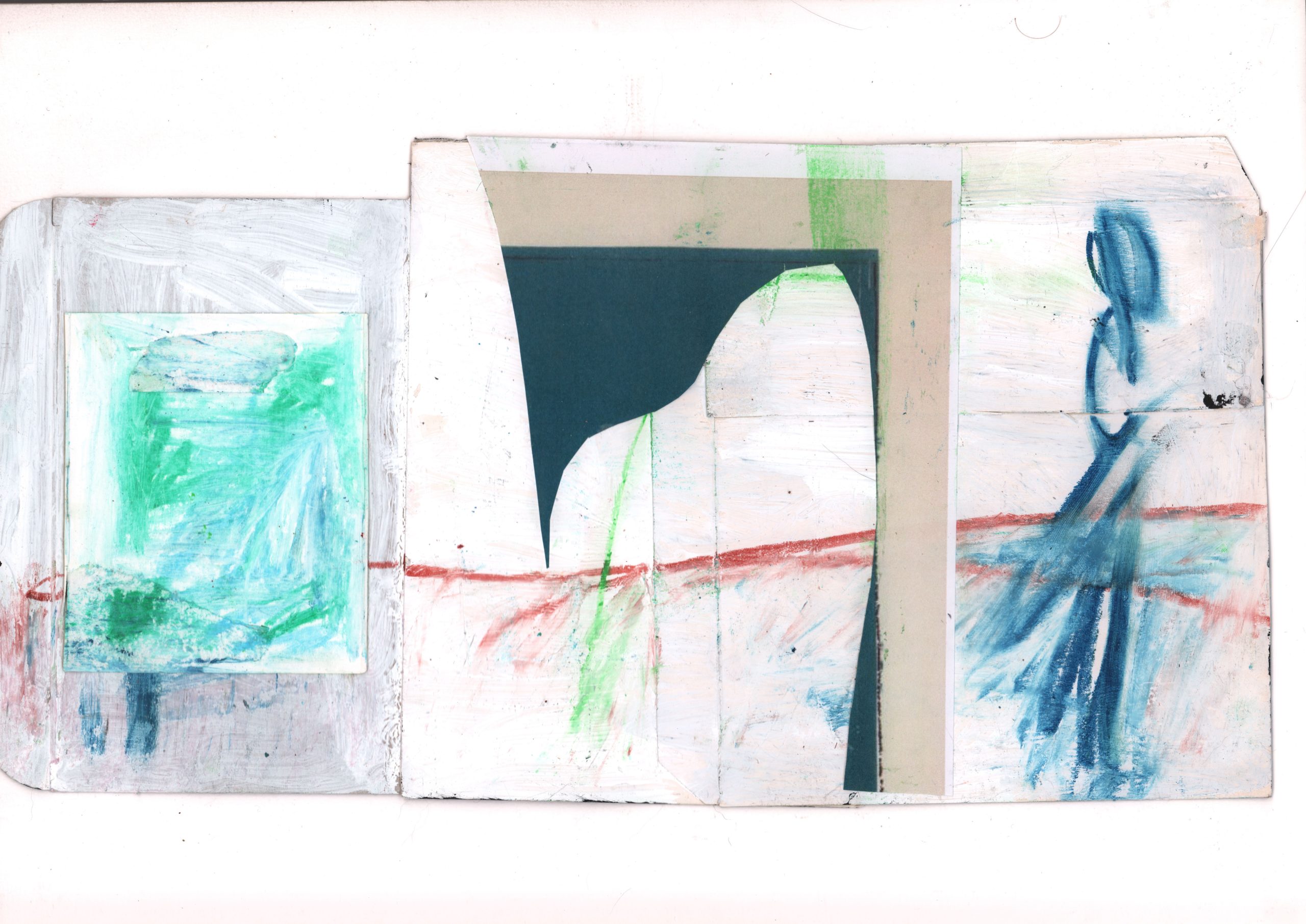

Cover image: Nadin Reschke, Oda Project, Words to Spin (2022)