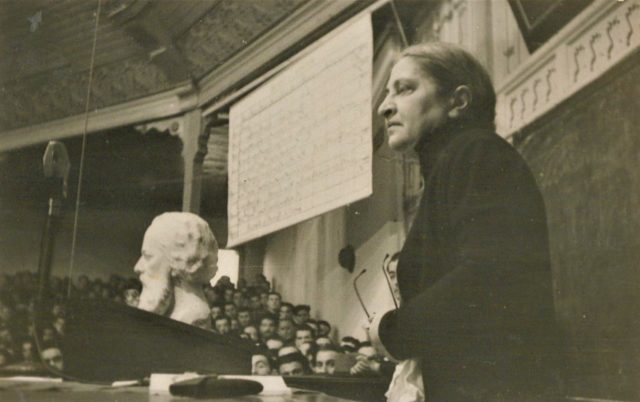

Nuriye Gülmen commenced her one-woman protest on November 9, 2016, in front of the Human Rights Monument on Yüksel Street in Ankara, a month and a half after she was suspended from her position at Eskişehir Osmangazi University. She was detained on the first day of her protest. Once released, she returned to the spot where she continued her sit-in under a banner that read “I was suspended, I want my job back.” She was detained again. The day after, she was back on the street. Her struggle with the police lasted days. As she insisted on her protest, of which she kept a diary, shared via her blog and social media accounts, the number of curious eyes around her and those who came for support and solidarity increased. What remains of the media that can produce news began reporting on this individual protest. The foreign media, meanwhile, showed great interest from the beginning. CNN named her one of “the outstanding eight women of 2016” on the 50th day of the protest. Surely, the attention she drew was not to go unpunished. Gülmen was dismissed from her position, from which she had earlier been suspended, with an Emergency Decree Law on January 6. And on March 8, she began an indefinite hunger strike together with Semih Özakça, a teacher also dismissed by an Emergency Decree.

Today marks the 143rd day of Nuriye Gülmen’s resistance on Yüksel Street and the 23rd day of her hunger strike. We asked her about how she came to decide on e this resistance, how she musters the strength to keep it going, and how her last six months have been.

Today is the 22nd day of your hunger strike. How are you? How is your health and morale?

Physically and biologically, I am fine. I’m on hunger strike together with Semih. We are both fine. So far, the only observable change in our bodies is the weight loss. We are fine otherwise.

It’s the 22nd day of the hunger strike but the resistance goes back a long way. You went out on the streets with the demand “I want my job back”. Can you tell us from the very beginning how you decided to start your resistance?

I was placed in the Contemporary Literature Department of the Faculty of Arts in Selçuk University in 2012 by the Council of Higher Education. Then, I was appointed to Eskişehir Osmangazi University. In 2015, I was dismissed from this university with the excuse of failing to finish my studies within the designated time frame.

Because you couldn’t finish your Master’s in three years?

Yes. The thing is, I had been arrested before because of a political lawsuit, after I started working at the university and started my Master’s. I was detained for 109 days. And after my release, my reinstatement was delayed, so this detainment cost me a year. Not to mention that I was acquitted. Yet Eskişehir University included the time I spent in detention and the year that I lost in this whole process in the period of study. So they discharged me. Later, I filed a suit and I won. I went back to work, but my reinstatement took seventeen months. The lawsuit itself lasted for a year and I was delayed to get back to work for another five months. This coincided with the coup attempt and the declaration of state of emergency, during which period I started working at Selçuk University. I was suspended the day after I started working there. In short, I went back to work after a seventeen month absence and was suspended a day later.

Did you say “I’ll begin protesting out in the streets” as soon as you were suspended? What was your decision process like?

This is a process with a history for me, going back to 2015 and my first dismissal. I went through similar situations before my dismissal. While I was working at Osmangazi University I was subjected to severe psychological harassment, intimidation and mobbing. Many times, I was prosecuted due to my participation in the Gezi protests. I received huge penalties for all of them. I was always working under a threat of dismissal. They left me with no energy for academic study. I did a lot of work to resist my dismissal; I prepared for the hearings, tabled on the street and collected signatures in Eskişehir. So I had that practice. When I was dismissed again, after I won the lawsuit for which I struggled a lot, that was it, the tipping point. Of course the fact that they did this as part of a FETÖ/PDY prosecution had something to do with it too. It was as if they were mocking me. I was certainly going to take action against this.

Also, I had lots of friends around me who were signatories of the peace declaration (initiated by Academics for Peace). I wasn’t working at the time but was still following it closely. There was a huge assault on academia following the peace declaration. This, too, had a vital significance for me. But of course, as I was not a direct subject of that process, I only participated, to stand in solidarity with them. Then, after first my reinstatement and then my dismissal, my own process began.

What did you have in mind when you went out onto the street? A protest that would last a few days, a few weeks perhaps? Or did you plan to sit there until your reinstatement?

Yes. I know this way of protesting. I wasn’t the first one to do it after all. This is part of a revolutionary tradition in Turkey. It is a style of protest that carries on until it gets results. Our protest is in fact a continuation in this tradition of resistance. You want something, you demand something and you carry on until you get what you want. You are prepared to pay the price, you do if necessary, and you win in the end. It is impossible to win your rights in Turkey any other way. This is true for any protest that succeeded.. It is unyielding. It comes under attack but it perseveres until the ultimate point, and wins. For this reason, I always had in mind a resistance that was resolute, something carried out with such determination. That is how I stepped out on that street. I never thought I’d be there for a day or two.

What about standing out there on your own?

In fact, I did some work in advance. I went to many towns. I met with academics, especially with those who were signatories of the peace declaration. I reached out to those who were suspended, dismissed and prosecuted in this process. I told them about my idea of this protest. I invited them to do it together. The one and a half months after my dismissal was spent on such efforts. Unfortunately, there did not appear such energy, a concrete step from there. So, I began on my own.

And you have been on that square for 142 days now. How many times were you taken into custody?

I think 27. Or rather, the police attacked the site 27 times, I wasn’t here once. So it must be 26 times.

I guess the police, too, understood that the detentions did not have an intimidating effect.

Sure, they know it. They are aware of the determination I spoke of in the beginning.

Did you imagine this protest would grow and get so much support? That once it started, it would reach so many people?

No, I wasn’t expecting this kind of reaction. Protests like ours happen all the time, people carry out such protests for their jobs or for other rights. However, they rarely receive support on such a scale. To tell you the truth, I didn’t have any idea it would be heard, embraced this much. I wouldn’t have even imagined. In a state of emergency, where there wasn’t even the meekest voice while many were experiencing the same thing, the appearance of a single woman was effective. I suppose that’s why it garnered so much attention.

Why did you decide to go on a hunger strike?

For months, the will to continue this protest in spite of the cold, the winter, and the arrests was always really appreciated. The hunger strike is the continuation of this determination. It’s not something very different. We sat here for 120 days. I am not an Ankara resident. But since The Council of Higher Education is in Ankara, the capital is the place where my demands are to be met. I came and devoted myself to the resistance. Before the hunger strike, we used to stay four and a half hours everyday at the site. But staying in a different place every day, living with a backpack, spending every moment speaking of and giving voice to the resistance… Indeed, except for sleep, the whole time was dedicated to the resistance.

I got engaged in this action both with a claim to win and with great devotion. You see, the price was quite high. The arrests, and a life that is completely changed… At one point, the protest reached saturation. And despite all the attention, no reaction came from the state, from the authorities. I am sure they hear and know of all our demands. They know for sure, including the president. They know, but they turn a blind eye. However, they cannot ignore a hunger strike. This is not something they can turn a blind eye on. It was necessary to take the resistance to the next level. This is what we can do. We believe this will really pressure them to take action. That is why we decided to go on a hunger strike.

How do you spend your days now?

As I said, we used to stay at the site for four and a half hours each day. With the hunger strike, we changed that to 24 hours. We don’t sleep at the site, we go in turns to a place nearby to rest and we return in the morning. Semih and I arrive at 9. By the way, there are six of us who are in this resistance. Aside from me and Semih, there is Acun Karadağ, a teacher who joined the protest in its early days. Veli Saçılık called himself a supporter for a long time, but he went beyond that and became a very important part of the protest. Esra Özkan Özakça joined, she was suspended and reinstated, then was dismissed. Finally Mehmet Dersulu, who works in Yumurtalık, Adana, came after he was dismissed. It’s six of us now now. But because the protest now continues in the form of a hunger strike, everyone other than Semih and I are working actively to make the strike heard.

We are at our spot from the morning on. We leave twice during the day for an hour to take a rest. It is less crowded in the mornings, so we read. Newspapers, books arrive. By noon, Yüksel Street and Kızılay Square get very crowded. People start passing by. From that moment onwards we speak of our protest nonstop. You see, we did not retire into the shadows just because we are on hunger strike. We keep up with the tempo of the former routine of our protest. We explain ourselves to the people, we hand out leaflets, collect signatures. We make our statements to the press every day at half past one and again at six. People got used to these hours so they join us. We have visitors.

In terms of visitors, do you experience unexpected encounters?

A lot. Let me tell you one that I cannot forget. A young woman, quite young, came and said: “I had no hope in life. I was in a deep depression. Then you came about, started a protest here. And I held on by following this protest every single day. And on the first day I managed to get out of the house, I came here to you.” This is one of the most striking examples. But there are hundreds of people who speak of the value of what we are doing. They rain down messages on us from social media. For example, after an arrest, people crowd the site so much more the next day… After Semih and I began the hunger strike, we were arrested and held in the political bureau of the police station. During those five days, while we were absent, people came to claim the site. There was a beautiful crowd, I saw in the photographs.

Everyday, since you started the protest, you write updates on your blog. We followed them for a long time on nuriyegulmendireniyor.wordpress.com.

Yes. Now there is also direniyoruz.net, which is more up-to-date, and it includes all such protests. As you know our resistance spread to other towns as well. If I am not mistaken, in nine places – maybe eight, after Betül left Kalkedon – there are ongoing protests. Nazife Onay in Istanbul in front of Cevahir Mall, Engin Karataş in Bodrum, laborers who work in the public sector in Aydın, Erdoğan Canpolat, Sertaç Ökdemir, Özkan Karataş, Cengiz Uğurlu in Malatya, architect Alev Şahin in Düzce, Mahmut Konuk and Cemal Yıldırım in Ankara, Barış Bozkır in Didim. Our website was launched recently. Shortly there will be daily updates on the Website, of new developments in the protests going on in these towns. For example, in Malatya they have been continually taken into custody for over seventy days but the protest moves forward. Everyday there are police attacks. They are taken into custody every day. Our friend in Bodrum suffers the same fate. Nazife Onay in Istanbul is continually taken into custody, and each time she is detained for a day and is taken to the prosecutor’s office.

You gave hope to so many people by going out on the street. To conclude, I want to ask you if you’re hopeful. How was it in the beginning? How do you feel now?

They always ask me if I believe I will win. Let me say this: This is not something one can do if one does not believe. You wouldn’t be able to stay here even for an hour if you didn’t believe. I do think that hope is something that can be created. Even if you are on your own. You do something, some people start believing in you, in what you do. Other people are influenced by that, and this gives birth to hope. People sense this.

It spreads…

It spreads. For this reason I am much more hopeful than I was on that first day. Our resistance is greater today. We are thousands of people who harbor the same hope.

Çeviri: Ö.T.