It’s been more than 10 years. Stemming from my admiration for Alejandro Jodorowsky, a part of me was idealizing the connection of healing arts to the power of cinema. A few years ago, as I realized this idealization of arts masked the malevolence that is an integral part of the human condition, I bid farewell to this naïve side of me. During that time, I also realized that rape was not only an exertion of power but also an attempt to steal another’s innocence. Then, I heard Leonard Cohen’s other-worldly voice saying: “If you are the healer it means / I’m broken and lame / If thine is the glory then / Mine must be the shame”.

It was a striking coincidence that during the same period as we were globally coping with illnesses, I learned that Jodorowsky’s healing is no different than the hodjas (Islamic religious teachers who use magic to supposedly heal the ill, but who mostly turned out to be fraud and abusers) who claim to be practicing exorcism when they are actually harassing women. Just as I sat down to write about the disappointment I felt in another male “hero”/artist/auteur, I’d put it aside because I was concerned that the subject matter would not resonate with anyone, as everyone was alarmed by the pandemic. Then, the following happened: In addition to cases of zillions of not-so-famous harassers/rapists, three famous cases of harassment and aggression – of an academic, an actor and a comedian- were made public by women. A feminist professor of philosophy had the audacity to call Sara Ahmed a “cult leader” for her liberating/empowering views, such as the feminist killjoy, and this philosopher called trans activists a “cult” and a “herd” for raising their voices with reference to Sara Ahmed. On top of all that, there was an article published in Altyazı full of praise for Jodorowsky’s “healing cinema”. For me, Jodorowsky lies at the intersection of all these discussions around healing, cult, abuse and arts. Taking all these into account, I went back to writing the piece that I had started months ago.

Et tu, Jodorowsky?

I thought I no longer idealize an artist. It’s as if there is a part of me that refuses to grow up, when I idealize anyone. The admirer, at times, sees the admired as a parent, and other times idealizes the admired like a distant star and objectifies them. It seems to me that, in any case, there is the inability to establish a real connection or a meaning-making mechanism. That is not to say that my disappointment stems from my blindness as an admirer, but somehow, it is related to it.

When we talk about a “cult film”, we don’t necessarily talk about the film itself but its viewers, or rather its fans, and how they put the film on a pedestal. In sum, if a film is considered cult, the person who likes the film becomes a disciple/cult member. In this context, El Topo (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1970) fits this described category – and watching the film is compared to participating in a “cult!” ritual. In fact, we are talking about the film that gave “Acid western” genre its name. It was commonplace to find viewers taking LSD and watching 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick, 1968) for the sixth time at a movie theater while tripping between the dimensions of “collective consciousness”. It is rumored that El Topo had a similar effect, and there was a group of people who flocked to a movie theater in New York every single night for a year. John Lennon had bought the distribution rights to El Topo. Dennis Hopper, who has a cult icon status himself, loves El Topo. Not only did Jodorowsky directed, wrote the script of and produced El Topo; he also wrote the scores to the film and co-starred in it alongside his son. “You are seven years old. You are a man. Bury your first toy and your mother’s picture.” El Topo starts with these words. El Topo gallops anima and animus around. El Topo not only encompasses Freud and Jung, but also embraces all sorts of outcasts and underdogs. El Topo overflows with compassion, atrocity, curiosity, critique of the bourgeoise, anarchy and psychoanalysis. El Topo was the film that made me believe in the healing power of cinema.

These praises might be alienating to you, that’s perhaps why the film is considered a cult picture. We tend to find cult members peculiar. I must have been one of those disciples of Jodorowsky during my PhD. My colleagues, like me, had studied films and found sustenance in watching movies for years. Just like many other cinephiles, we had forgotten about the amazement of finding a film that was truly innovating and original. With the release of the DVD edition of El Topo, Jodorowsky appeared out of nowhere from the 70s – for us to meet one of the most unconventional directors I’d ever known, and the most spirited critic of Hollywood. He was almost as multi-talented as Eisenstein not only as a director, but also as a theoretician. He was half Chilean half Russian, whose films and co-theorization of the Theatre of Cruelty with Artaud attest to his never-ending compassion. He was a surrealist, a healer, a graphic novelist, and a tarot master.

Let’s fast-forward to ten years later:

As I was discussing film noir and the studio system in Hollywood in the 1940s with my students, I was also passionately taking a dig at producers, since Weinstein was sentenced to 23 years in prison the night before the class. Beforehand, I had my students watch Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944), so they were busy condemning Wilder’s sexism. Our discussions led us to the conclusion that the fault not only lies with the studio system, but also with the entrenched auteur-centered perspective that determines the film to belong to only one creator. Looking back, I realized that just a week before Weinstein’s sentence was announced, rapist Polansky was awarded the best director prize, and Adèle Haenel had walked out of the ceremony hall shouting “Bravo, the pedophile”. During that weekend Elif Rongen-Kaynakçı and I had criticized the patriarchy in auteurism.

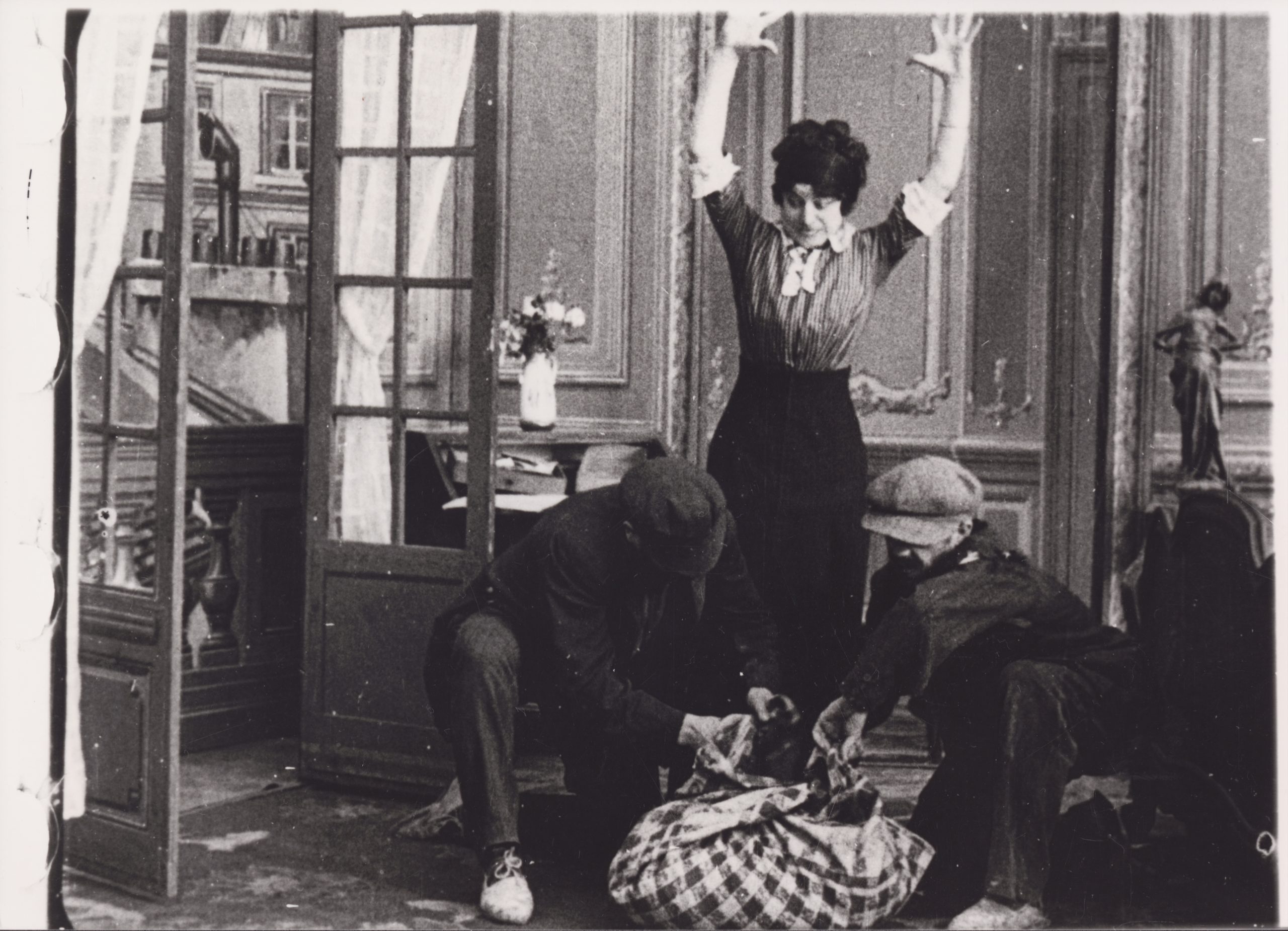

Mara Lorenzio, as she is walking towards the phallus statue, a replica of Jodorowsky’s penis, designed for El Topo.

You end up treating the individual as a god when you assign an art form as multidimensional and powerful as film to a single person’s creativity. That’s why you don’t want to deal with the ego of a director. Besides, if you look at the canon closely you will see that it is exclusively composed of men, except for token directors such as Agnes Varda, Chantal Akerman or Jane Campion. But I want to turn my attention to my reckoning with the curriculum I created, or rather, how I happened to write to 5Harfliler about the thoughts I had as I was leaving the classroom: “Although I try to include as small number of studio films as possible into my class curriculum, I was not able to completely give up on auteurs. We think that harassment suits producers because they have access to capital. Although we sigh with relief at the sight of Weinstein, the “intellectual and independent” auteurs who have taken a similar predatory route still retain their high regard.

I tend to stay away from directors whose harassment history is out there, but films like Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960) or Europa (Lars von Trier, 1991) can still find their way into the curriculum. That’s exactly why I have to question auteurism as much as I question the studio system as part of cinema education. After jotting down these sentences, I started to prepare for my graduate class. I was going to discuss why we have to move away from a phallocentric psychoanalysis with my students who were already fed up with Freud and Lacan. At the same time, I was reading what Jodorowsky said about the rape scene in El Topo shared by a colleague in the UK. It made my blood run cold:

“When I wanted to do the rape scene, I explained to [Mara Lorenzio] that I was going to hit her and rape her. There was no emotional relationship between us, because I had put a clause in all the women’s contracts stating that they would not make love with the director. We had never talked to each other. I knew nothing about her. We went to the desert with two other people: the photographer and a technician. No one else. I said, ‘I’m not going to rehearse. There will be only one take because it will be impossible to repeat. Roll the cameras only when I signal you to.’ Then I told her, ‘Pain does not hurt. Hit me.’ And she hit me. I said, ‘Harder.’ And she started to hit me very hard, hard enough to break a rib… I ached for a week. After she had hit me long enough and hard enough to tire her, I said, ‘Now it’s my turn. Roll the cameras.’ And I really… I really… I really raped her. And she screamed. Then she told me that she had been raped before. You see, for me the character is frigid until El Topo rapes her. And she has an orgasm. That’s why I show a stone phallus in that scene… She has an orgasm. She accepts the male sex. And that’s what happened to Mara in reality.”

The interview is from 1971, a year after the film’s release. The film returned to movie theaters in 2020 following its 4K restoration. Some of the screenings were cancelled with the initiative taken by my aforementioned colleague or other conscientious film people. Although you can find this interview in the DVD commentary and in Jodorowsky’s book, I wonder how no one paid any attention to this ‘detail’ until recently.[1] Jodorowsky made a statement following the cancellation of a screening in New York. He claimed that he did not rape [her]; that his intention at the time of the interview was to provoke people; and he acknowledged what he had done as problematic. Let’s say he did not “really” rape her and he is remorseful for underestimating “rape”. What are we to do with his assertion that Mara Lorenzio was healed through rape? Or the fact that he attributed the female character’s inability to reach an orgasm to her refusal of male sexuality? Or that he denied Lorenzio her power by exhibiting that he is not hurt while being beaten up by her. Following that, the rape is “real”-ized amidst her desolation. He is deceiving us by idealizing arts as holy and curative while maneuvering the space between fiction and reality. Isn’t he playing a wretched game, with the psyche of a woman who has expressed that she had been raped before, for the sake of his art and capacity to heal someone else? Then, there is the sophistry around raping a woman until she reaches orgasm.

A surrealist director can compound the reality of his life (and in this case, his co-starring son’s life) with the reality of cinema. With the ego of a healer/guru, he can believe that he is the sole creator of reality, too. It might suit someone perceived as the sole creator of a film to intentionally blur the boundary between fiction and reality. But when the blurred boundaries of art violate someone else’s reality and body, the validity and reality of “consent” becomes questionable.

The boundaries of a “genius”/”guru” and a sociopath may be intertwined, but it is more common to call an “auteur” a genius. Perhaps, Lorenzio never made a statement, for she looked like she gave consent to rape at the very last moment. Maybe she accused herself for saying yes to rape even though she was being manipulated. I wonder if she was able to watch the film which ran for a year at the movie theaters. Has she read Jodo’s proud statements saying, “I really raped her”? Did she believe that she was broken beyond repair because her rapist, the filmmaker, is alleged to be a healer? At least we know that she never talked about this issue in public. And it looks like she did not partake in any other film. The “shaman” and the cult director made his last film about his healing powers. But what happened to Mara Lorenzio?

Mara Lorenzio during the rape scene

Since Jodorowsky treated rape in line with the “requirements of his cinema”; there is no need to promote him further during a time when one can no longer – not even Woody Allen – take refuge in middle class morality obsessed with the distinction of public and private life. Instead of watching Psychomagic, A Healing Art and give credit to a “healer-auteur” who brutally violated any dignified boundary and obscured reality, I’d rather listen to “you want it darker / we kill the flame” by Cohen. I’d recommend you do the same.

There are feminist academics who do publish on this. See Jaramillo, L. (2020). Ritual, Cult Spectatorship, and the Problem of Women’s Flesh in Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Midnight Movies. Feminist Media Histories, 6(3), 172-206.

Cover image: A scene from El Topo.

Translated by Deniz İnal. To read the article in Turkish please click here.