This year, the month of May hasn’t only heralded summertime with its hot, merciless sun; its more sluggish oscillations in the streets and in places of business; its jingling crowds out on breezy evenings, maybe swimming a few lengths out in the sea; the sweaty rush through the daytime, daydreaming as you go about from one place to another. No—at the last minute, May whispered to us of the possibility of a night that time had set aside. A June on the brink of a plurality of possibilities knocked at our door. We were home waiting, and we ran to open the door.

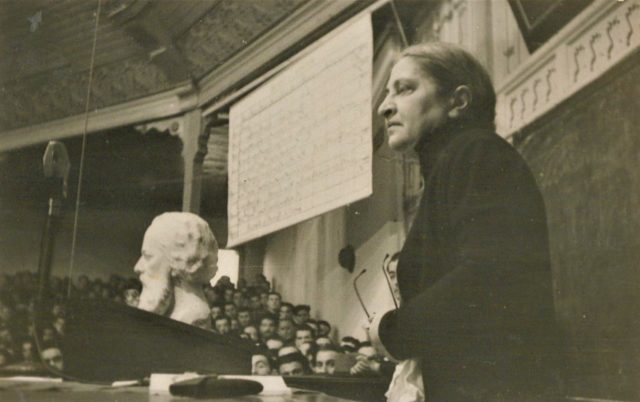

Now they’re looking out on this June standing on the threshold, this June we were waiting for so long. Now they’re trying to interpret a June that came without being called. There are all sorts of hot takes, morning and night, day after day on TV and in the papers and on the Internet, page after page after page. They do all kinds of analyses, belittling every subject under the sun: Gezi, the AKP, popular uprisings, the “masses” who form the “backbone” of the resistance, the police state, “who is this ’90s generation?”, social media, partisan politics, people who sell flags made with quality fabric, “how will the resolution process be affected?”, public space, urban transformation, unearned income, “what the hell are all these gangs?”, lifestyles, and so on and so on. Without even getting up from their armchairs or changing their haughty tone, expert sociologists and psychologists and political scientists and savants and academics and newspaper columnists and conspiracy theorists and specialists in every field under the sun are all presenting their detailed analyses of that June that we’d felt like thunder.

June’s reckoning will be going on for years—discussions, arguments… And it should go on. It should go on so we’re no longer stuck in the pincers of some worn-out sociology that’s managed to whittle away at itself again and again. But still, this is upsetting. Men and women whose only expertise is being an expert smugly explain to the state that very thing whose every wondrous, feverish moment we experienced ourselves. Speaking and giving advice to the state and the state alone, they use their glowing cat eyes* to become counselors to the state, coaches for the ruling power—and this brings up a whole different kind of anger. And regardless of whether they stand together with the state or are lined up against it, there are some things that those “enlightened” people trying to explain what went on in the streets, squares, and parks (without ever themselves actually going to the streets, squares, and parks except to make observations) can never get across to the state with that “objective,” aloof, and oh-so-expert language of theirs. How can they possibly interpret anything about how for a month we stood on the threshold of timelessness, about what we wrote and what we created, or about what we experienced? For they experienced none of it themselves.

But sometimes we fall into the same trap, too. We ask them, “Haven’t you had enough of analysis?” But as we sit to do our own analyses we end up, every time, selling off emotions. Violence and oppression on the one hand, the state keeps turning about on our tongue. Forcing us to speake “rationally” and with only its own reason. We vomit up some grandiose stately spiel. Forums are infested with new parties being founded, elections, ballot boxes, the AKPs and the CHPs, and the moment we start talking as citizens of the state the ground of conversation slips out from under our feet.

But the June that we lived through is now just a nice bit of information disclosing itself to those who tasted it, touched it, felt it on their skin. There’s no need to give it a name, but that doesn’t mean we should forget that we learned by feeling it. That’s why I want to talk about the feeling that has enveloped this last month, about my own feeling, even if it doesn’t involve or represent or even concern anyone else.

“You must all know the night of the deer

In distant forests green and wild

When the sun sets slowly where the asphalt ends

It will deliver us all from time”

This poem by Turgut Uyar has been going round and round in my mind since the first day of the resistance. It gathers up into itself a whole mass of feelings and instincts I can’t name, and seems to tell me why there’s no need to name them. They were saying, “Fear’s threshold has been crossed” and answering the question, “Why can’t the masses be dispersed even under all this pepper spray?” And on the night of May 31, in Harbiye, as that first big crowd walked toward the bitter cloud, took two steps back, and then moved forward again even bigger—on that night the first lines of “The Night of the Deer” were being written for me:

“Yet there was nothing visible to fear

Everything was of nylon, that’s all

And when we died, we died quick, five or ten thousand against the sun.

But before we found the night of the deer

We were all as afraid as children.”

Like Turgut Uyar’s “we,” we were ourselves an imminent “we,” and truth be told our imminence was as unsettling as the gas and the police. Even as we cried out, “Arm in arm against fascism!” it was obvious that the person you were arm in arm with at that moment might switch tomorrow to some other fascism called patriotism or honor, had in fact already switched, so now you’d have to find some other “we” to stand arm in arm with, now against his fascism. This was as clear as could be—and yet there, at that moment, the crowd in the midst of that cloud of gas was “us.” And it was exactly because we were so many that we could be there, stay there, refuse to disperse, and take one more step forward on our way back toward Gezi, ever bigger after getting pushed back two steps. As we got the news that people everywhere had taken to the streets, that they’d walked across the bridge, everything about the day before or about the daytime before that night or about, like, some 9–5 work schedule—all that started to seem more and more made “of nylon.” I don’t know if “fear’s threshold had been crossed” but that night and afterward, when Gezi was “ours,” I could no longer go into or even fit inside houses or buildings, since I’d now had a taste of being on some kind of threshold, I’d tasted a dash of possibility. And it wasn’t because, as they’d go on to write, “We thought we’d started a revolution.” Nor was it because, as the phrase went, “This is a people’s resistance, a people’s revolt” or something even more significant. Instead, it was because there was a sense of retrieving something lost was lost…

According to the experts, it was “the ’90s generation that was the heart, backbone, center, and core of this mass of people,” but I still haven’t really known how this generation lived. I think the feeling I’m talking about is more of an ’80s feeling: the feeling of being born into defeat, into a gray state; of being born into the arms of adults carrying a bleak and heavy silence on their shoulders, a silence under whose burden they had collapsed. To be born a few years after the coup (or maybe even right into the coup) made it feel as if you brought a curse with you, and you grew up with a sense of guilt. That gray gloom filling the air had once been almost green, like all the stories about a time just before you were born… As you walked in all seriousness around adults waiting for the evening news behind their rectangular glasses, you could hear their joyous laughter only in those moments that commemorated that particular past… And all this grew and grew, turning the gray into something more than a color. Alright, so now we’re adults now, too, and now we understand how and why they did what they did, we’ll give them that—but let’s be honest, they inflicted something on us. The sentimental songs they belted out had worked their way into our marrow: they grew up and the world was ravaged. We missed out on the pure, the good, the green. There was nothing easy about growing up longing for something we’d never experienced, about being raised with a bizarre sense of resentment over being deprived of something we’d never even had. Our mothers and fathers and aunts and uncles remembered living the prime of their lives with a sense of joy, with the excitement of being on the brink or threshold of possibility, with the pride of being part of some “we”—but then they had to grow up with us, because of us, and they left their youth behind, lost their “we,” and were left alone. This drew an uncrossable line between us and that past. And then, as the ’90s came and did what they did while we grew up, that line became known as “the Özal kids.” Yes, Özal was the first politician we knew, so what were we supposed to do?

The glowing cat eyes of the analysts will of course notice how this ’80s feeling I’m talking about corresponds to a societal category; they’ll define it and fix it in its place, immobilize it. There will be data: defeat and Yeni Türkü, these are political; rectangular glasses refer to a class; the loss and loneliness of the post-’80 “we” will have their ethnic composition clarified; and it will be pointed out how these data are valid only for who knows what fraction of the population. And that’s exactly what I’m saying. Who knows how much. But this “we” I consider myself a part of was out in the streets, ready to come together with other “we”s with their own desires, quests, and grudges in order to put together a new “we” that might start to create some possibility. Because at Gezi it was attempted, and when there are many, many people a door can be opened, even if only a little bit, so that the night of the deer can begin to show itself…

I know this all sounds far too romantic. And I know that putting a name—a sociological, political, historical name—to whatever it is that was attempted over this last month turns it into a matter of greater seriousness and significance. But for myself, I didn’t take to the streets all “serious” so that I could become part of some category or fulfil some historical responsibility. The night of the deer that Turgut Uyar described at the end of the ’50s was a harbinger of going after something that was undetermined, impossible to catch and hold on to, even utopic—but still it was something that those who understood the possibility would go after regardless of the impossibility. And the reason I couldn’t stay cooped up inside but had to take to the streets was not because of any longing for something that came before “us” but rather because today, for the first time, I had had my first taste of that possibility. This taste is political, no matter how romantic it might sound, and what’s more, it’s a possibility where for the first time the political is not for the state but instead for that “who knows what fraction of the population.”

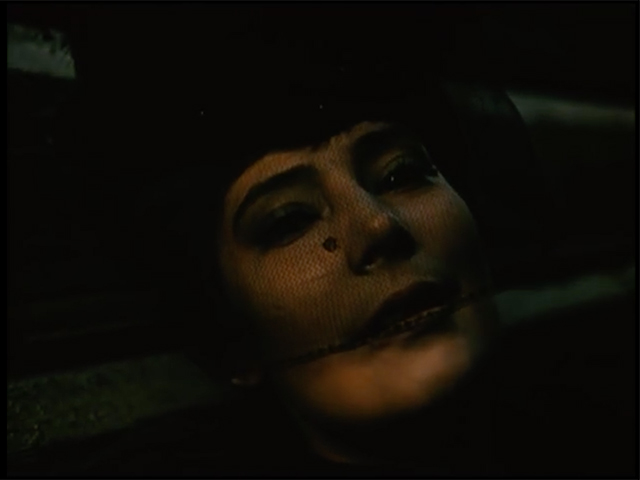

At the end of “The Night of the Deer” Turgut Uyar leans forward and kisses himself on the cheek. Now, maybe for the first time, we understand the poem as a way of crossing the line dividing us from what came before us, as a rejection of taking shelter in the nostalgia of the victimization that comes with never being able to be true agents, and as an attempt at individuality in the midst of multiplicity. “We” are just one “we” among dozens who have grown up since the day of our birth developing grudges against the state and its processes, and who have now learned to all share our grudges in common. There’s no need to give it a name, but we shouldn’t forget that we learned by feeling it. They can never identify the place that aches in us when we see the picture below**, nor can they ever translate to a statist mentality the feeling we have now, when we smile a fresher smile precisely because of that pain.

*”Glowing cat eyes” is a popular meme about Gezi. Phrase was first used by the popular Turkish actor Necati Şaşmaz in an utter nonsense speech after a group of “artists” held a meeting with Prime Minister Erdoğan in an effort of mediation between the activists and the government.

** During the 80s “crying boy” image was so popular in Turkey that he was staring at you with his sorrowful eyes everywhere from the walls of the living rooms to the long-distance busses. Nurdan Gurbilek, in an essay named, “Acıların Cocugu” (The Child of Sorrows) interprets that enormous interest in the image in years following the military coup (1980) as a self-reflection of society as a wronged child, who has been drained of all strength but is still standing.