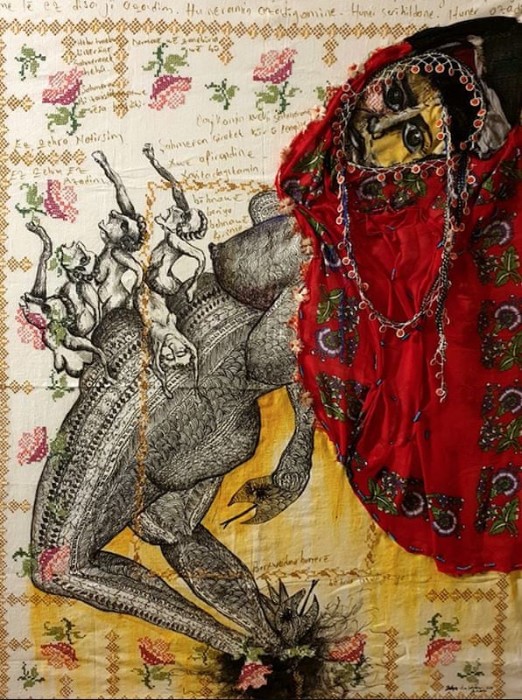

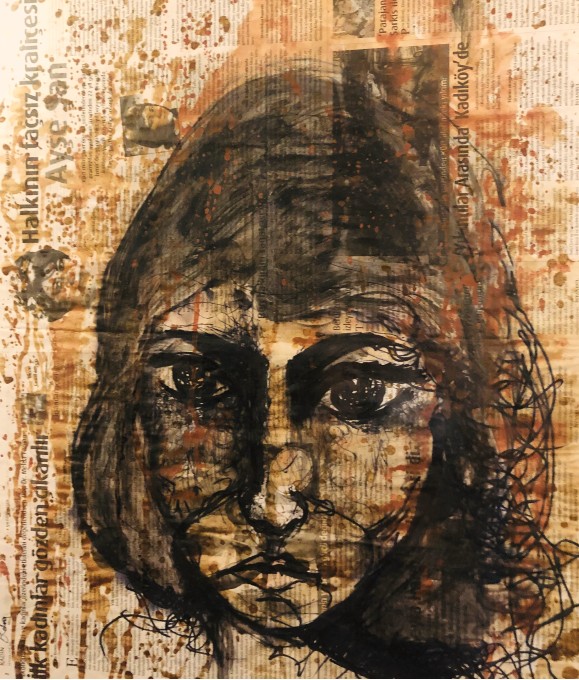

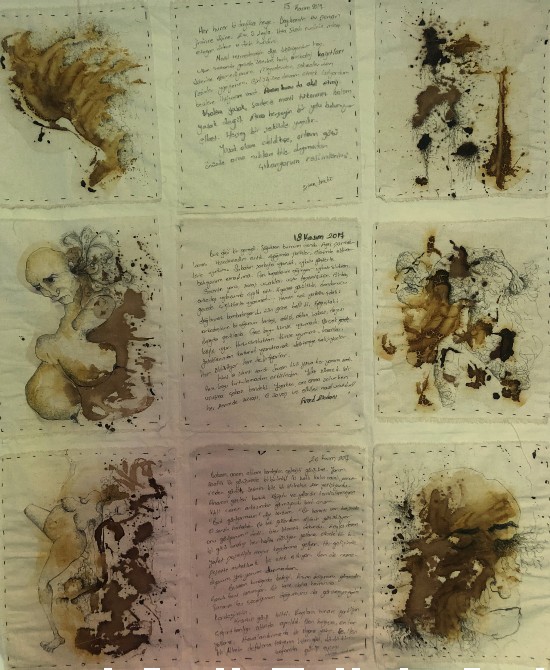

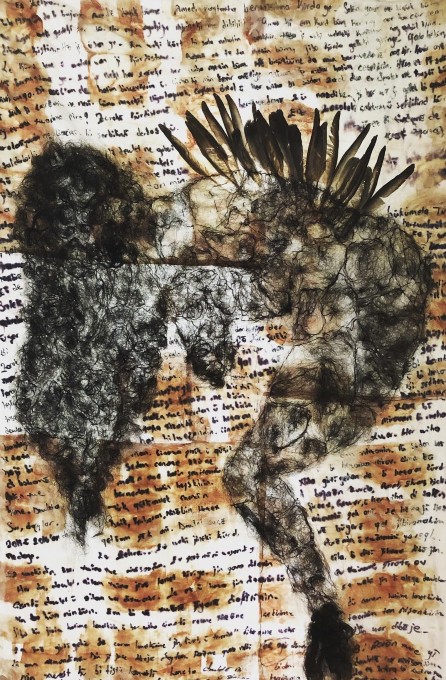

Zehra Doğan’s first solo exhibition in Turkey “Nehatîye Dîtın / Görülmemiştir” (Not Approved) took place at Kıraathane İstanbul Edebiyat Evi from October 9 to November 9, 2020. Works at this exhibition were all created with limited means during her imprisonment.* Among the materials she used to create these pieces are: bedsheets, dresses, newspapers, letters, and dyes made from fruits, tea, coffee, and period blood. One of the most impressive works at this exhibition were the ones co-created by Zehra and her mother, who continuously tried to replace the materials taken away from Zehra. The ingenious system they established worked like this: Zehra’s mother sent in the skirts and dresses she has sewn as part of ‘clean laundry’ with the prison guards. Then, Zehra dyed and treated these clothes, and returned them to her mother as ‘dirty laundry’, again, with the prison guards. It was an act of feminist solidarity, and a mischief against the system- trying to pierce a hole through its walls.

To solely focus on works Zehra Doğan produced during her imprisonment would mean to imprison her again – so we decided to touch upon a variety of subjects ranging from her life story to her installation at the Tate Modern for this interview.

Who is Zehra Doğan?

I was born in Diyarbakır and grew up there; but my family is from Mardin. I grew up in Bağlar, a highly politicized district. I have been painting since my childhood. If you were to ask me who led me to painting or sparked that interest in me, I would not be able to give you a direct answer. I started my training in painting at the age of 11 when I found out about the Mesopotamia Cultural Center (NÇM-MKM), an initiative of the Kurdish struggle. My family did not know about my training there. Due to the political and economic circumstances we were in, a training in arts was never in their purview. Following the university entrance exam, I wanted to try my luck at the fine arts academy exam, but I did not tell my family. My friends later informed me that I passed the exam. That’s how I enrolled in the Painting Department of Dicle University.

Your first solo exhibition in Turkey focuses on the works produced during your incarceration with limited means. Could you tell a bit more about these works?

The nature of prison dictates the limited means available. We’d experienced further restrictions in prison with the declaration of the state of emergency. For example, no red or black pens were allowed- you could only use blue pens. It is true that there are many restrictions to your arts practice in prison but there is a tradition. When their books are confiscated, people write down the pages of the book on pieces of paper to make sure others can read them. In a way, they are re-writing the books. You might be familiar with imprisoned writers like Selahattin Demirtaş or Gültan Kışanak but there are many others. While they were a source of motivation, the short length of my time in prison also helped. The first time you enter the prison, the walls start weighing down on you, and you cannot get accustomed to that. I don’t think anyone ever fully adapts to that atmosphere. It’s more like coming to terms with the fact that you are in prison and relating to the outside world despite those walls. I accepted the fact and tried to create things from the found materials. From this perspective, each of these works were like a stone thrown at those walls to break them. They were a means to restore my connection to the outside world.

Did you start recognizing the materials around you after you came to terms with your circumstances?

I did not have an ‘Eureka’ moment because I knew about the artists who have been engaging with this type of production since the 1970s. My works must stand out because I produced them in prison. I was inspired by the works of feminist and protest artists who work with found materials. I used materials like bedsheets, tea, coffee, turmeric, arugula, tomato paste, period blood, bird feathers that fall to the open-air area, and my falling hair- but I did not restrict myself to applying one material on another. I started designing dresses at Mardin Prison. I identified each of these dresses with friends of mine. For example, I could only explain who İncile Anne is and what she means to me through one of these dresses.

One of the most interesting found materials that you use is the period blood. Was it difficult to turn that into a material you could use?

Period blood has quite a significance for me, too – but not for its qualities that can be exploited as a material. Conceptually, I find it very powerful. Through the works where I used period blood I was putting the warden, prison guards, and people with power to test. As they were trying to limit my materials and extend restrictions over my practice, I was able to retaliate with a material that was my own; something that disgusted them. In order to make sure they touched it; I rubbed that blood over letters I wrote. They were appalled and disgusted by that. But I should have been the one who was reacting that way since I was imprisoned there, and they were even reading my letters. I associated them with virus in computers. These letters had to pass through the hands of the Prison Reading Commission regardless of how disgusted they were. They were repulsed by the fact that they had to touch them, but it was my right to send these letters. And, they had to hold them to read them.

Tarsus Prison

How did your friends react to your use of period blood?

After a while, they started sharing their period blood with me. Actually, it was a collective idea. Youth and mothers alike, they were comfortable with the idea. It was an interesting experience for me and them alike. I got to know about menstrual cycles of everyone there. We’d put papers under the wardrobes and drip period blood on them, then leave them to dry. This process made me closer to my body. To get your period used to be a matter of disgust and shame. That’s what the society dictated for years. We had to keep our period a secret and made sure no one saw the pads in our pockets. I learned a lot from the creation process of this work. I started to question these [behaviors/attitudes around menstruating], then others joined me in this rather powerful act.

Artwork labels at the exhibition tell us that solidarity of your mother and sister was indispensable for you to make art while in prison. Could you tell a bit more about this solidarity? What have they done for you?

One day, my paintings were confiscated during a search. We came up with the idea when we were talking about the confiscation with my mother- we were going to bring in fabric as if we were exchanging dirty clothes for clean ones. Of course, the fabric would be in the form of clothes. Like a skirt or a dress. Then, I was going to dye the fabric. It was not only my mother, but also my sister, sisters-in-law, neighbors- all of them organized a tremendous women’s solidarity. My sister bought the fabric, mother sewed it up, sisters-in-law and neighbors embroidered them. For example, they embroidered beads on a fabric to send in the beads. It is rather long and tedious to embroider beads on fabric one by one. That was very impressive, it was as if they were digging up a tunnel. I felt that some people were digging up the other end of the tunnel. It was rather ironic that the prison guards had no idea what was going on in front of their eyes and they even took part in the exchange.

They never noticed?

They never did, and we’ve repeatedly done it. I used to give my dirty clothes (art works) to the prison guards, and my mum returned clean clothes fabric and other materials. We, my mother and I, exploited the absurdity of it all – by using the labels and job descriptions embedded in the system, its monotony and uniformity, to break through it.

It is striking to see patriarchy testing your limits in your works. Could you tell a bit more about the types of difficulties you faced as a woman?

I wouldn’t call it a difficulty but there is definitely something tiring about it. The attitude of men, especially men involved in arts that see themselves as the proprietor of a certain field, manifest their condescension through remarks like “I am the absolute best in this field,” “Political arts? Hold your horses,” “You have not earned your place yet.” I know it for fact that if I were a man, they would not reproach in a similar manner. They are constantly acting as if women need their approval.

You need to treat men nicely and make sure they are on your side so that they say nice things about you. Or, maybe, you must befriend them.

I assume since you were imprisoned, you did not have the chance to create that space for yourself, even if you wanted.

Yes, my experience evolved independent from these dynamics. I was, unfortunately, in prison and somehow my works started to attract attention. With Banksy’s support, there were more people talking about me. Then, I was released from prison and bypassed their approval. I saw this coming. I worked at JINHA for years. I saw how men manipulated projects and women, without admitting to the fact that they were using and imposing their privileges as a man, when women start achieving things. I used to interview and document cases of women who experience similar things. I knew very well what to expect. I also knew that men were not going to accept their faults.

My experience at JINHA and Kurdish women’s struggle taught me what is going on, and I am not uncomfortable with that. But, like I said, I get tired from it. When you think about it, there is nothing about me that should trigger them. I am Kurdish but, according to them, I did not graduate from a good university, my family is not rich, and they did not guide me to get a formal training in arts. If anything, I kept my nose to grindstone to get to wherever they deem I am. I was young when I was prosecuted for throwing stones and received a six-month prison sentence. I was taken into custody multiple times, and mostly recently, arrested. I spent my childhood selling water, parsley or sweets. Some people might call us [where I come from] “ignorant”, I know that’s how they see us. I used to earn my own pocket money as a kid. You asked me whether I remembered painting for the first time, and I could not give you an answer. I used to dye shoes, would that count?

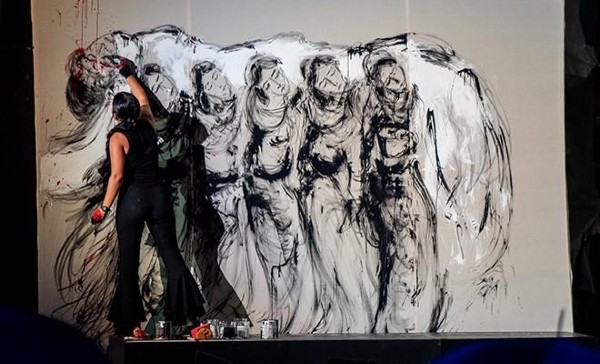

How did you end up in Tate? Could you describe how it felt to have one of your installations there?

It was interesting because, as you rightly call it, I ended up in Tate. I was just released from prison when I received the invitation from Tate Modern. I wanted to install a piece on which I have been working for years. I wanted to exhibit destructive forces of state there, which is the reason I was prosecuted. It was very important for me to go there with my personal testimonies, experiences, records. I believe there is a critical threshold here, I am Kurdish but if I were not in Nusaybin during the curfew, I don’t think I would be able to produce this work. It is not enough to be Kurdish to undertake such a project. I brought what I witnessed and remembered to Tate as a subject of these events, along with those of my friends and acquaintances. The platform Tate provided added visibility to this destruction, which felt good.

What’s next for Zehra Doğan?

To tell you the truth, I don’t know. I was never able to make and stick to a plan. I don’t really think about where I want to see myself in the future. If I were to make a plan, and it does not pan out the way I planned, I don’t put myself down. I want to stay true to myself. I would like to be able to pursue a project I believe in, after having dedicated months or years to my readings and research. It is rather important to provoke some people through the arts, but I do not want to limit my practice solely to that. I would like to stand by my comrades, especially the women in our common struggle. I would like to preserve my heritage because I feel good about doing that -and that’s enough.

*Journalist and painter Zehra Doğan was charged with being a member of an illegal organization. Among the evidence against her were her social media posts of the paintings she created during the curfew in Nusaybin and the news piece she put together from the notes of a 10-year-old. She was acquitted from the charges brought against her during the first court hearing on December 9, 2016. She was released on the same day to be later tried for the accusation that she was spreading terrorist propaganda. She received a 33-month prison sentence and was taken to Diyarbakır E-type Prison Facility in June 2017. She was released on February 24, 2019. Doğan made her debut in the international art scene with her installation “Ê Li Dû Man” (Left behind) exhibited at Tate Modern in May 2019.

Translated by Deniz Inal.