We met with Rebekka Endler, the author of The Patriarchy of Things, on the occasion of artist Azade Köker’s The Murder of a Mannequin exhibition catalogue launch in Istanbul. Rebekka Endler studied Social Sciences in Cologne and Freiburg, Germany with the idea of gathering knowledge about society to write detective stories. Instead she found that one of the biggest crimes is patriarchy and that detective stories weren’t her medium to change that. Today, she is a freelance journalist and radio producer based in Cologne. Her first radio story about a white US cop and his wife adopting Black children won the RIAS Radio Award for best transatlantic journalism in 2017. She is the author of “Das Patriarchat der Dinge” (Dumont 2021), a bestselling book about patriarchal design in everyday life.

Rich, white, cis men get to be served. The city is designed for them. What are your examples for this? What is patriarchal design?

My definition of design is very broad, everything “man-made” is designed and therefore serves an intent and purpose (at least in English, even the word “man-made” is an example of the androcentric design of language). So patriarchal design refers to creations that center around the cis male experience, which can be found everywhere. Cities, the design of our public space in general, are a good example, since how safe, comfortable and mobile a person is, is a reflection of their privileges. Not everyone is equally welcome to take up space in public. Take the simple example of sidewalks, I noticed their defectiveness all the time in Istanbul. How broad are they? Does a stroller, a wheelchair, a walking aid fit? Do they inexplicably end in the middle of a street, or turn into stairs, making the space inaccessible for anybody disabled or traveling with a baby? In which case, it is very likely that it was designed by a not disabled-bodied man, who has never done care work for a child himself. The implicit message is: If you can’t navigate here, this is not your city. Another simple example are curbs. In Cologne, where I live, the curbs are lowered for every garage entrance to make it convenient for cars to drive into, yet on street corners, where it would matter for pedestrians they are often not, making it challenging to cross if you are incapacitated. In Germany, post second world war, we have designed our cities around cars and we have neglected the needs of every other group, such as pedestrians, children and cyclists. Since cars are driven by more adult men than any other group, everyone not in a car is merely an afterthought. Other examples would be lighting, distribution of public restrooms, public transportation, the culture of monuments. All these areas of the public space are designed to accommodate the needs and wants of cis men.

As an ecosystem, the patriarchy has many ways to manifest itself starting from the choice of words as you talk about in the first chapter of your book. Also, we know for a fact that patriarchy leads to femicide. How do you think this range of multi-layered suppressions add up to constitute a patriarchal understanding?

I think the question is: how the fuck did we all end up in patriarchy in the first place and how do we get out of it? The dutch anthropologist Carel van Schaik writes about patriarchy as an anomaly in human history that makes up for only three percent of all human history, obviously the last three percent. He also thinks we are coming close to abolishing this era, and there is nothing I would like to believe more. But how?! Unfortunately van Schaik is not very specific about the how to’s, so I tried to fill some of these gaps in my book by looking at the problem through the lense of design, although it is by no means a practical guide to abolishing patriarchy. One historic problem seems to be a knowledge gap. We’ve all learned Frances Bacon’s quote about “knowledge is power” but actually there is also a lot of power in willful ignorance. There never is any action maxim as the result of something you do not bother to know. That is one of the reasons data collection in areas such as medicine, transportation safety and car design, workplace design, sports (the list goes on) show such a huge gender gap in knowledge. It is not an inconsiderate oversight, it happened by design, by patriarchal design aiming at suppression. There are several examples of knowledge, what was once acquired and transmitted through female scholars such as midwives around childbirth, was lost in, or —more accurately— eradicated by men in Western medicine in order to maintain and gain power. Another reason is evidently capitalism, which feeds off and thrives in the exploitation of women and other marginalized groups. So our challenge is not only to collect as much knowledge as we can, but even more importantly we need to build systems to perpetuate and canonize knowledge, so the future generations can build on top of it. Virginia Woolf wrote about this a hundred years ago and it still holds true, so much power comes from canonizing and building systems to support the work of women. I would add that it holds true for intersex and non-binary people, queer people, Black, Indigenous and people of Color and disabled people, every group that is systematically marginalized is equally important in this endeavor. If we can manage to do that, van Schaik might even be right and we can overcome the system that kills us.

The second chapter of your book is “Who owns the public space?”. Really, who owns it and who doesn’t own it?

The concept of public space is that by definition it is public, so by definition it belongs to the citizens. Except, we don’t value and welcome everyone in the same way. Just as every other area of life, such as the private home, the work space, academia etc. the public space is a battlefield of power, and a very important one, since it’s the most visible one. One obvious aspect is the storytelling through monuments and street names. Who do we deem worth honoring? And what is the story? Monuments always tell the version of the winners of history, never those who were oppressed and robbed of their power. But we are now witnessing a change. For example we’ve been seeing monuments of Christopher Columbus and Confederate Generals being taken down in the US all of last summer, in Europe we are finally reconsidering our history of the 19th hundreds and taking down monuments honoring colonialists and war criminals. The consensus about who deserves to be remembered evolves over time and a power shift away from the white man to a more diverse storytelling of history is tangible in a lot of places. We are reframing our history and of course this does not just happen, it’s the work of activists, who little by little shifted the public opinion.

You say we need to “instigate conversations about [these] mechanisms outside of academic discourse and our own progressive bubble.” Can I ask how?

Ah, so much would be gained, if we had a solution for that! What I have noticed with my book promotion is that it’s a matter of having little fires burning everywhere, getting people to talk about the aspects that are easy to connect with, because they are rooted in our everyday lives, rather than rooted in an academic discourse. Examples are easy to come by: the problem of finding a safe place to pee, or not dying during a car crash or a heart attack. Even people who would never pick up a book, much less a feminist book, might hear me talk on the radio or on tv about it and speak to their neighbors about it. Ideally some sort of social pressure builds up and politicians feel the need to address issues. In Germany this is starting to happen, yesterday a politician of the Green Party said, she wants to make the development of a cis female crash test dummy mandatory. Obviously there is no way of knowing, but I’d like to think that this is some kind of ripple effect of people having pressed this issue in the media during the past months.

You were recently in Istanbul for the catalogue launch of Azade Köker’s exhibition Murder of a Mannequin at Zilberman. What are your observations about the city within the framework of your findings as to patriarchal design?

Istanbul, canim, as much as I fell in love with you and I did, you seem to be a tough place to have and raise a child in. The first time I came here was in 2015 and my daughter was five months old, the hassle I went through trying to find a place to breastfeed her or to change a diaper in public —I don’t know how parents do it! And I won’t start again about sidewalks that are dead ends or curbs or trash bins blocking paths, but this is clearly a city that fits the needs of not disable-bodied, childless people, men best. But my views are limited to my own experience as an able-bodied white woman with a lot of privileges. If one would really want to improve the city design, you’d have to collect data of all the people who live here and ask for their wants and needs. And, of course, in a historic city, which wasn’t developed on a drawing board, it is extra challenging to accommodate for everyone, but there is a lot that can be gained from including these groups in the design and making accessibility a priority. The positive effects of an inclusive design have been well documented in academia, it has proven to increase the quality of life of all citizens, not just those who are affected by it directly.

Last question: There are also examples of creative intervention in public space, one of which is Women’s Garden (Garten der Frauen) in Hamburg, as you mention in your book. It is striking that Rita Bake came up with such a brilliant idea. What is this Women’s Garden? How do you understand this initiative coming from a historian?

Rita Bake, the historian, who came up with the idea and who has spent the past 20 years curating the cemetery was one of the first historians to put a number on the dominance of men in the public space, because she was the first to come out with official public statistics on how many streets, monuments and public buildings in the city of Hamburg which were named after prominent men, and how few after women. Numbers are important, they are hard evidence of the imbalance that is otherwise just felt. After that she has led multiple efforts to have streets renamed (especially those named after highly problematic colonial criminals), or streets in new neighborhoods named after women. So she had already been attuned to the gap in public representation for a long time, when she witnessed the demolition of the grave of Yvonne Mewes, a public school teacher who died in a concentration camp in 1945, after having been a figure in the underground resistance in Nazi Germany. As a spontaneous act Bake took Mewes grave stone, saved it from being turned into gravel and thought to herself: “Okay, this is the only object left to remind us of a woman the rest of the world has already forgotten about. I need to find a place to keep it in public and also to tell her story.” Evidently the most obvious place for a gravestone is a cemetery, so she petitioned the city to be allocated a garden space for her project: Women’s Garden, a cemetery, but also a walk through history told by women. The shift to a female perception is ubiquitous, patriarchal parameters such as achievement are redefined, so that can read about amazing nurses, nannies, secretaries, but also revolutionists, sex workers, artists, all women who on their own terms contributed to a better society, although they might never have gotten any recognitions during their life times. It is history reframed, through an anti-patriarchal lense and the fact that this garden is part of the biggest cemetery in Europe opens it up for a lot of people walking through there, who would otherwise never engage with anything remotely feminist. It’s taking feminist ideas and creating an engagement with the public that happens on a practical level without academic discourse —something a book, or a museum exhibition can never achieve in the same manner. That’s why public space plays such a crucial role in my understanding of changing public perspective and why we need more places like the Garden of Women.

To read the interview in Turkish please click here.

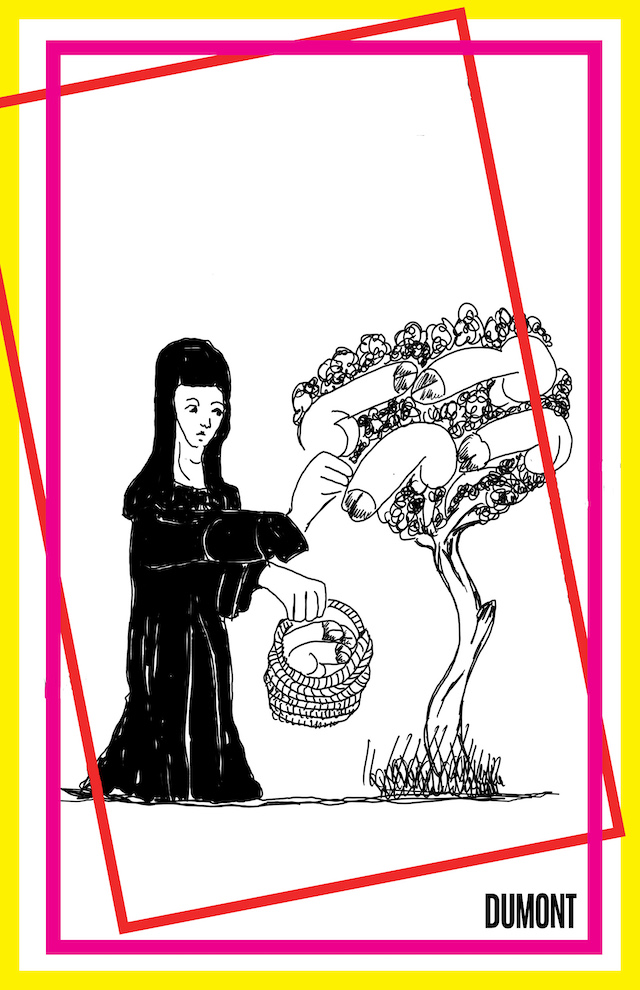

Cover image: The drawing of the nun collecting penises from a tree is an illustration originally done by an artist named Jeanne de Montbaston for the Roman de la Rose France in the 13th century. While often (male) art historians have argued that de Montbaston was probably illiterate and therefore had no idea what Roman de la Rose was about (it’s about a misogynistic dude comparing the act of writing to the act of penetrating a women with his penis and therefore, writing could only been done if you own a penis), other (women) art historians have pointed out that the illustrations could also be read as a satirical commentary by de Montbaston (“Oh hey, I know you need a penis to write, but look how many penises grow on this tree, I can just take a whole basket full of them, if it pleases me”). But since women were not supposed to have any sense of humor, ever, the second explanation is still not accepted by most as an also likely option.

Images in the text in order of appearance:

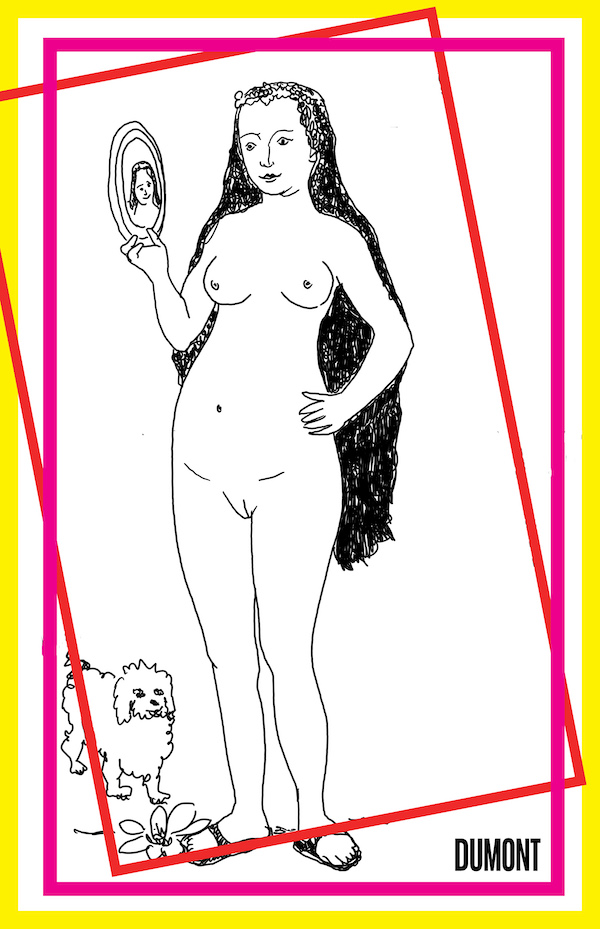

- “Vanity in selfie modus” is from a painting by Hans Memling from ca. 1480 and it has been used by art critic John Berger to explain the male gaze: “You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting ‘Vanity,’ thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for you own pleasure.” Today the same mechanisms come at play when we talk about young girls and women taking selfies, although I would argue that although I am still uncomfortable with taking selfies in public (thanks topatriarchal socialization!) there lies a great power in authoring your own self picture.

- The four ladies dressed as lollipops are taken from one of the very first movie videos ever made (long before this was its own genre that sparked MTV, Viva, etc.) in 1966 for France Gall’s song “Les sucettes,” authored by Serge Gainsbourg. Gall had just turned 18 and had grown up so sheltered that she didn’t know until after the song came out, that Gainsbourg had had her sing a song about blow jobs. She became the laughing stock of the entire nation, while he was celebrated for the innuendo. It’s from a chapter of how culture has had a way of monetizing the so called innocences of young women all through the present, even at the expense of scaring women for life. At the same time the construct of virginity, purity and innocence have become capitalist goods keeping real equality in sexual behavior at an unobtainable distance for most societies.

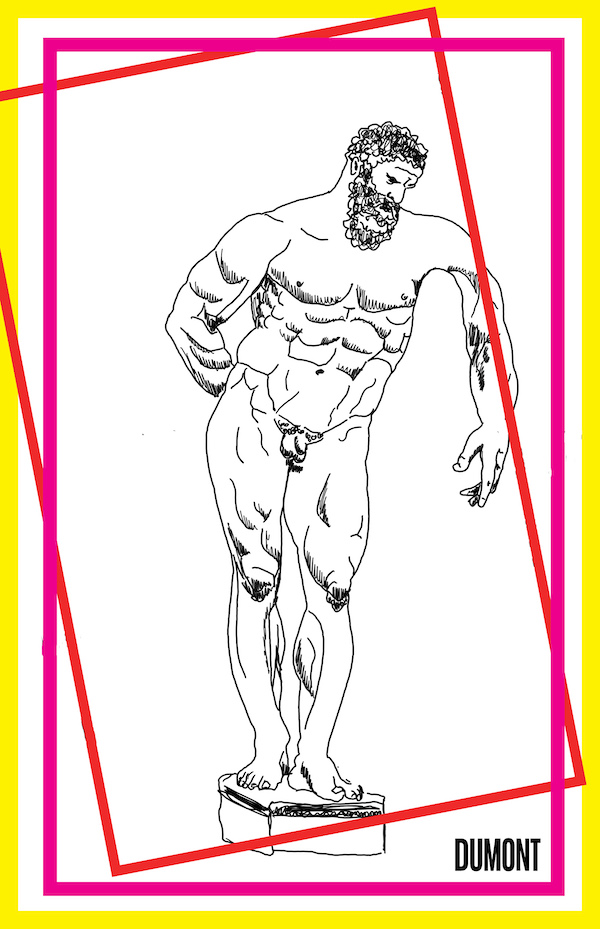

- Hercules and his micro penis are from the chapter about language constructions. In so many western languages today courage is associated with “having balls,” or “cojones,” although this is a relatively new concept. In ancient Greece too, there were rivaling ways to look at cis male genitalia in order to tell character traits. All the great heroes, gods and half gods are depicted with a small junk, because it was believed that this was a sign of great virtue (as if your penis gets in the way of virtuous behavior, which is still to this day a popular way of excusing shitty behavior). But at the same time there was also a tradition of less virtuous, but hyper-masculine super potent men, who were described as to have huge genitals. So, it’s complicated, but so much of these believes about how genders have to be performed have found their way into our language and perpetuate this understanding of gender differences. (I really can’t judge for Turkish, but I can speak for pretty universal finding in most European languages).