According to the calendar, it’s been a while since spring started, yet here I am writing as I watch snow falling on solid soil that’s just starting to loosen up here and there. Who would believe it? It’s snowing on a spring day, right before my eyes. I wouldn’t have believed it till I came here. I’m glad I came, glad I saw, glad I believed.

But the real question is, how did I get here? For anyone who doesn’t know, let me talk a little about the procedure. On that soul-sucking test called the Civil Service Entrance Examination, once you’ve managed to secure yourself a place in the pecking order, there’s an agonizing period where you have to choose. Out of the hundreds of schools, you weigh maybe forty or so alternatives, pick them out, write them down. And then the waiting starts. And as soon as the results are announced, you start looking for a ticket to a place you’ve probably never been before and where you’ll never go again if you’re not assigned there. But at this stage you’ve got to be quick: you might want to fly there, but the tickets are gone fast! And then you end up like me, stuck with a bus ticket.

Two or three days after the results are announced, you have to rush off, since registration starts right away. Yes, so there we are, off on an adventure where we don’t know what’ll happen or who we’ll encounter. Our mom’s by our side—but we’re sitting by the window, as any real traveler should. The whole big bus is shared among fresh young teachers and their mothers and fathers. That’s how my journey begins.

We go past roads and houses, past mountains and streams, past goats and shepherds and threadbare fields, past chimneys that churn out smoke and chimneys that don’t, past Syrians going in the opposite direction, past gendarmes and police, past boys going off to the army and mothers with tears in their eyes, past the raucous escort of drums and shouts following behind a pickup truck. We keep going and going, and as I see all these things one by one, I come to my senses. Or rather, I kind of find myself, I seem to start understanding myself. And I’ll keep on finding, keep on understanding. A couple lines of verse come into my head and stay there. They’re by Cemal Süreya[1], and I know they’re going to be there, in my head, till the day I die: God, did you make this long Anatolia / When you were just a child?

So my fellow traveler and I go through long Anatolia, by towering mountains and unending roads, till we get to some small district’s even smaller subdistrict. Now I really understand Ferit Edgü’s lines, and what’s between the lines—in Wounded Time he asked a question he didn’t want the answer to: Don’t you know these mountains have rocks for trees? This sentence will always remind me of that city with its face turned toward Lake Van, its back resting on the rocks. No matter how I got here, that’s how I’ll remember it.

I don’t know if arrivals like these always happen toward morning or if that’s just what’s always happened to me, yet just before sunrise there we are, in the district capital. Nothing stirs in the market or the streets, where men reign supreme. Naturally it’s only much later that I’ll realize that here, the world belongs to men, and that anyone from outside stands out like a sore thumb. It’s September—the weather in these parts has long since started to cool. We’re sitting having breakfast in a café where, during the day, a crowd of men will pull their chairs out to the edge of the street to take up their duty of watching everyone going by. A café where a woman just walking by is barely even tolerated. Of course, this is also something I’ll only learn later. (I can still feel the tranquility that came with first seeing into this social phenomenon.)

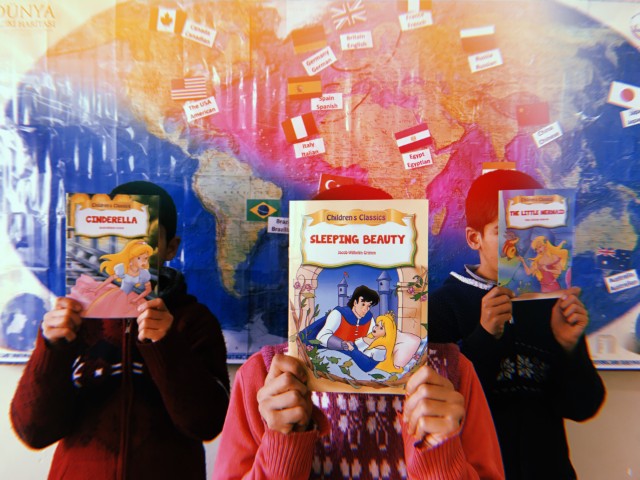

After hours of traveling and that first random morning we finish up our official business. And that’s how I came to the city where I’d spend several years of my life. But it wasn’t just years—it was a period of time that would upend the whole foundation of my life from then on. Who can remain their same old self faced with those tiny hands opening up in front of you? I don’t know how to put these feelings of mine into words. These children whose hearts are so withdrawn, so timid… All they want is for you to see them. And you will see them, but they won’t even look at you. It’s been eight months now since I met them all, and I still can’t get them to look me in the eyes.

After all my years as a student sitting at desks and taking tests, and then coming to this place whose name I hadn’t even heard till I was 23 years old, could I ever have even imagined the unconditional love of these children who so fearfully ask you, when the first term is over, “Teacher, will you be back next term?” How could I know I would find notes left in my bag reading, “Please don’t leave us”? How could I know when I was coming here that they’d beg me to say something in Kurdish and then break into big, joyous smiles when they heard the broken sentence I sputtered out? How could I just think of this as a few years of my life and brush off these children who’d always unfailingly tell me, “Teacher, you’re so beautiful today!”—even if I’d left the house without so much as a glance at my face or hair in the mirror?

It’s one thing to know about the power of love, but quite another to comprehend it. Everyone experiences this in different ways—or rather, it’s only the lucky ones who get to understand the power of love. Yes, I think it’s only the lucky ones who actually get to touch love. As for me, I got that chance, just a little, and I found love in my kids’ eyes. But I was even luckier—I learned to express my love in another tongue: ez te hezdikim. It means “I love you.” Don’t be afraid to say it. I say it every day—every day I say a hundred ez te hezdikims. And it comes back to me.

Note: One advantage of Mount Süphan is our view of Lake Van as ca be seen in the main image. A thousand greetings from all of us to all of you!

[1] Cemal Süreya is a renowned poet and member of the Second New generation of Turkish poetry.

Translated by Michael Sheridan